Shanghai Street View: Colored History

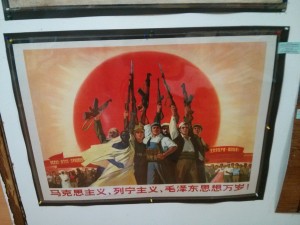

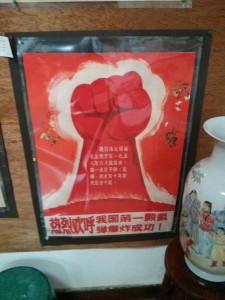

This week’s Street View took me to a leafy, residential area of Huashan Road where I went to check out a private museum dedicated to propaganda poster art after reading about it in the news. Housed in the basement of an ordinary apartment building, the collection of striking and boldly colored posters provided a fascinating look at China’s modern history dating all the way back to the 1950s.

Many foreigners like myself have a particular fascination with this kind of propaganda poster, which may partly explain why the popular TripAdvisor travel website ranks the Shanghai Propaganda Poster Art Centre as one of the top attractions for foreigners visiting the city. The museum gets little or no mention in most Chinese tourism literature, and even most mainstream foreign travel books don’t mention it, partly because it’s small and relatively new after opening in 2012.

My own interest in these posters comes at least partly from my interest in history. This kind of 20th century art gives a highly idealized view of the country that created it, reflecting how political leaders wanted citizens to see themselves and their nation at the time. Such posters also give a nice snapshot of national priorities at the time, as reflected by images like the memorable 1917 US poster of a finger-pointing Uncle Sam proclaiming “I want you” as part of a nationalistic military recruitment campaign during World War I.

I also love the bold designs and striking colors that propaganda posters use, which help to capture viewers’ attention and make for very lively wall art. I’ve always been a bit puzzled and even disappointed at the lack of enthusiasm for this kind of art among my local friends, especially since many Chinese traditionally have such a strong interest in history.

But I was also pleasantly surprised this time at the strong interest I got from a number of those friends when I posted photos from my recent excursion to the museum on WeChat.

I first read about the museum in a news report about a month ago, and finally made the trip when I had some spare time this past week. It wasn’t easy to find, located in one of the many blocks of an anonymous apartment complex on Huashan Road near Fuxing Road. I finally found it after getting directions from some guards at the entrance of the complex, and then following signs down into the basement of one building.

Despite the strong reviews from TripAdvisor, there were only around a dozen people at the museum when I visited, and many of those were foreigners. The owner, an older man named Yang Peiming (杨培明), had nicely divided his personal collection of posters into several periods, giving an informative introduction to the social environment for each period.

His collection even included some original dazibao, or “big character posters” from the turbulent Cultural Revolution period from 1966 to 1976. Not surprisingly, Mao Zedong featured prominently in many of the posters, as did a wide range of smiling and industrious workers and ordinary people from a wide range of vocations and walks of life.

Many people in the west find such posters attractive not only for their bold colors, but also their simple designs and clear messages. During a trip to the Soviet Union in 1986 when I was studying Russian in college, my classmates and I eagerly bought up dozens of propaganda posters in a souvenir store in Moscow, often for pennies apiece. The posters declared their vision for a bold future, and also cautioned against vices like alcoholism.

Local Russian friends we met were puzzled at our enthusiasm, even as we explained our intent to take these posters home and hang them on the wall as a form of decorative art.

More recently I traveled to the French city of Grenoble this past summer, where I was excited to find a number of local propaganda posters in an exhibition commemorating the 100th anniversary of the outbreak of World War I in Europe. Those posters featured similarly bold and colorful cartoon images, some vilifying the Germans, and others calling on young men to join the army.

Perhaps one reason many of my Chinese friends don’t share my enthusiasm is because this kind of poster art still exists in China today, whereas in the west it really does feel like part of history. Just the other day, I noted some new such posters on North Sichuan Road near my home in Hongkou District, discouraging people from making loud noises as part of group activities on the street that might disturb others – a common problem in Shanghai these days.

But I was also quite surprised and encouraged when a number of my friends, both younger and older, enquired about the museum and asked for its address when I posted some pictures on WeChat. At the end of the day, perhaps the appearance of this museum and others like it marks the start of a new trend that will see local Chinese join us foreigners with a new appreciation for these posters, which are both an art form and also an important record of history.